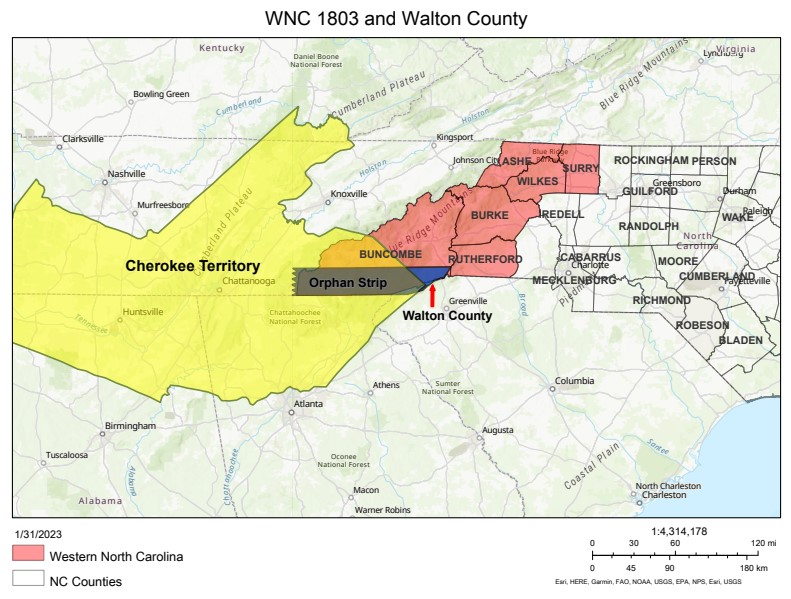

In Part II of this Picturing the Past series, the focus will primarily be on the extenuating circumstances which inevitably led to the Walton War. Historically countless wars have been fought over land ownership. While such wars were typically instigated because multiple sovereign entities wanted to claim the land in question, the Walton War is notable because multiple entities originally rejected the land: a swath of our own beautiful Transylvania County including the headwaters of the French Broad River.

The generally recognized reason for this uncommon occurrence was that the Orphan Strip was not the accepted domain of any state, thus it was assumed that the area attracted outlaws and banditry, especially considering that its original white settlers chose to settle illegally on land specified by Britain to be traditional Cherokee hunting territory and therefore off-limits to colonists.

As there was no governing body nor proper legal system in place, lawlessness and violence became the accepted way for residents to protect themselves and their property. Many years after their arrival, however, one of the earlier settlers described the influx of new residents as “a desecrated set that could not live in human society”, with those living in the adjacent states and counties complaining of robberies perpetrated by those inhabitants. Thus, none of the surrounding states wanted to be held responsible for the inhabitants or for trying to get them under control.

The volume of communication between settlers and neighboring governing bodies suggests otherwise, appearing to show desire on the part of Orphan Strip citizens for legal oversight. Ultimately, the truth of this is difficult to ascertain, mired as it is in spotty record-keeping and opposing reports, though overall the degree of lawlessness doesn’t appear anomalous compared to other area accounts.

Interestingly though, as undesirable as their neighbors may have thought them, it seems there was an understanding between the settlers and the original inhabitants of the area. A petition from residents of the Orphan Strip to Georgia’s governor details their concerns about their status on the indigenous lands and sending a man to a meeting of Cherokee clan chiefs to advise them regarding this. The message he returned to the settlers was as follows: “the result of the Indian Council is that we are their people and to continue on the land.”

While none of the surrounding states particularly wanted the land in question, that did not stop them from offering land grants within the Orphan Strip to Revolutionary War veterans. North Carolina’s attitude was that there was more than enough unclaimed land to fulfill grants from all surrounding states. Georgia offered plenty of grants of their own and South Carolina even got in on the action, though not in the same quantity as its neighbors.

Following the 1798 Treaty of Tellico, locating the boundary between Cherokee and Americans took on renewed importance. A flurry of surveys was completed over a five-year span to determine where the southern states ended and Cherokee territory began.

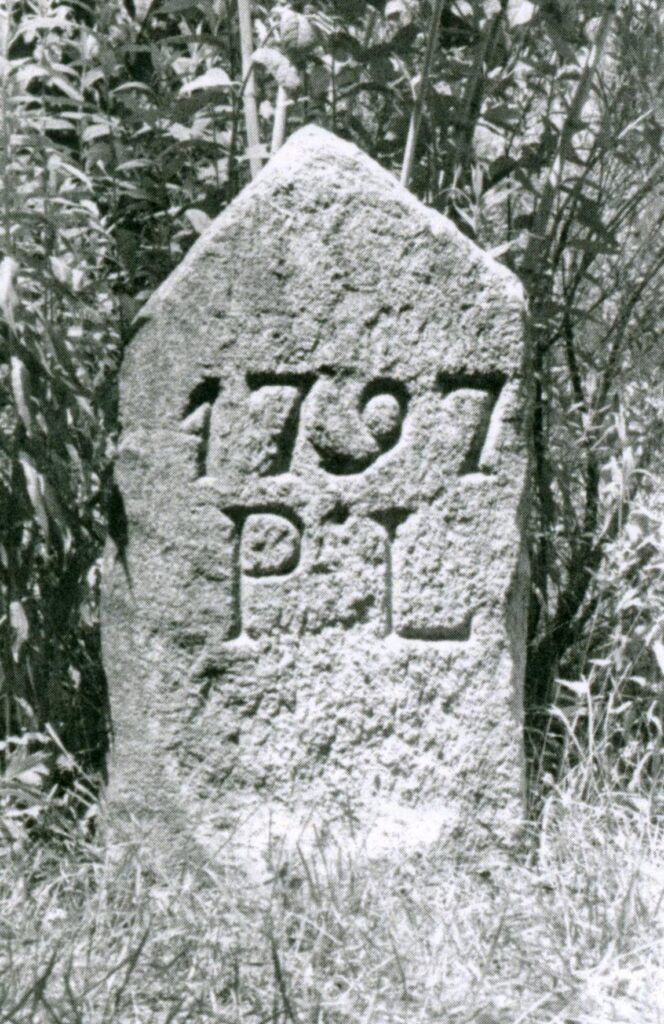

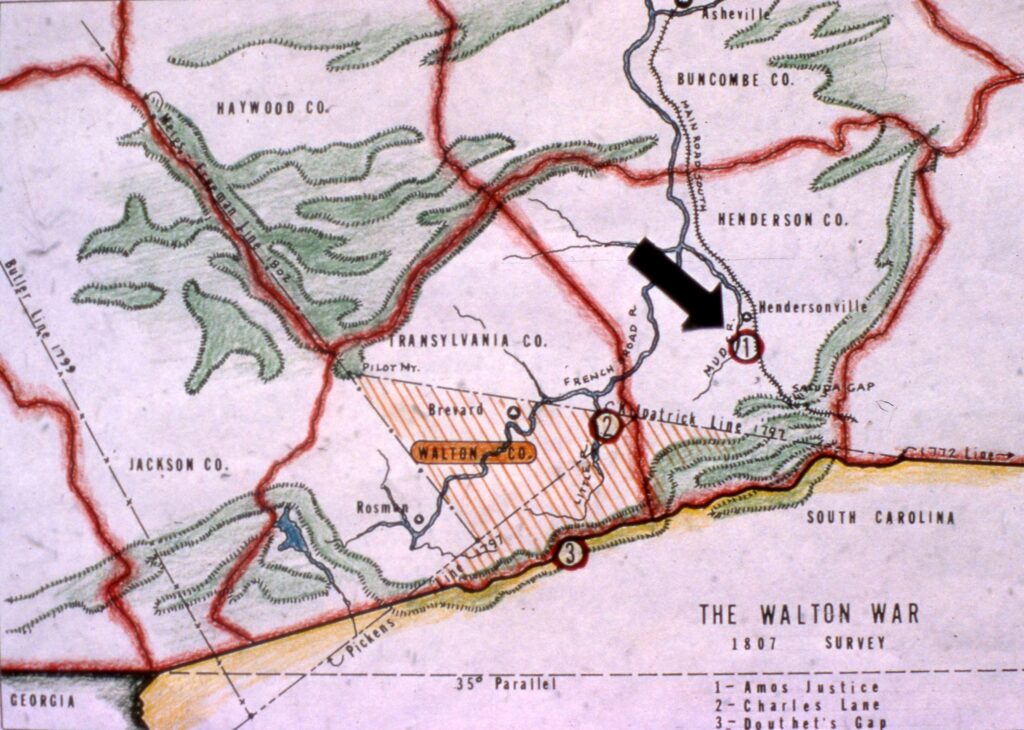

The first in 1797 was begun by Colonel Benjamin Hawkins and completed by General Andrew Pickens, often known as the Divisional Line. While running his section, General Pickens realized that the demarcation of the North and South Carolina border which had been resumed in 1772 didn’t extend far enough west to meet the line he was running. General Pickens dispatched from his team surveyor Colonel Kilpatrick to the terminus of the 1772 line—which had purposefully shot north by an unspecified amount to compensate for the previous underestimates of the 35th parallel—to extend it on a heading to meet the line that Pickens was simultaneously running. Kilpatrick’s line, which was supposed to travel only west, also had a distinctly northern inclination.

A survey of the northern boundary of the tribal lands was done in 1799 by Colonel Butler in an attempt to appease settlers who were upset that the Divisional Line had left them in Cherokee land; though his line seemed to overcorrect and placed too many Cherokee in the settler’s lands. In 1802 Colonel Return Jonathan Meigs was called upon to split the difference, his boundary line seeming to strike a happy balance between settlers and Cherokee.

Lawless or not, the Orphan Strip wanted a state to govern them, though which state varied among residents. Following an appeal by residents to Congress to be considered a part of South Carolina, a Congressional Committee offered the Orphan Strip to South Carolina as a gift which they refused surprising the committee. North Carolina seemed unaware that the contested land was part of what was then Buncombe County.

Georgia only finally accepted the contested lands—on a temporary basis—when it was tacked on to a larger deal with the federal government, the Compact of 1802, which paid Georgia a considerable sum of money while transferring to the federal government their liability for perpetrating the Yazoo Land Fraud. This was Georgia’s extensive legal entanglement resulting from selling fraudulent speculation grants for their westernmost lands, most of which belonged to the indigenous people of the area, rather than ceding them to the federal government.

Once this deal was struck in 1803 Georgia legislature directed Daniel Sturges, the state’s Surveyor General, to assess the borders of their newly acquired land, dubbed Walton County in honor of Georgian signer of the Declaration of Independence, George Walton.

Sturges came and went from the area in a remarkably short time to complete a survey. His purported finding was that the line of division between NC and GA—yet again, the elusive 35th parallel—appeared to be “at points that had long been supposed by South Carolina [to be theirs]”. The only reasonable explanation found by historians was that he arrived on the scene and discovered the survey markers left by Kilpatrick (marked PL, for Pickens Line), which were evidence of a line that had been run just six years prior, assumed it to be the line he was looking for, and promptly left, thinking his job done.

In a document submitted to Congress in 1803 defining the land they now controlled based on Sturges’ report, Georgia officials described their new county by referencing both the Divisional and Meigs lines, as well as the Cherokee boundary, the Blue Ridge mountains, and where they crossed the 35th parallel.

What was ultimately described in this official document, though, was a land that simply did not exist, as none of their reference points lay on the ground as indicated. This reinforces the theory that the resulting war stemmed from a complete lack of knowledge of the geography of the area then known as Walton County, GA, despite the numerous surveys that had so recently been completed.

The third and final installment of the series The Land No One Wanted and the Forgotten War will get into the meat of the events of the Walton War and its resolution over the following nine years.

Photos and information for this column are provided by the Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library. This article was written by Katie Silver, Venue Coordinator and Local History Assistant. Sources available upon request.