While researching an unrelated topic, my colleague pulled up the May 18, 1917, edition of the “Brevard News.” She showed it to me, and we were both immediately very curious. There were several cartoons and public service announcements urging people to “Swat the Fly!” and other various anti-housefly sentiments. More space was devoted to killing flies than a proposed German internment camp in Transylvania County, which certainly stirred up some controversy. Looking for earlier examples I searched backwards and other than a few articles in 1912 about flies spreading disease, there were no examples of housefly vilification in 1916 or before. A search of other newspapers during the same years revealed almost the same thing, except that anti-fly ads began appearing in more northern newspapers in 1916.

What was going on here? I started researching the housefly (Musca domestica). Medical historian Vincent Cirillo has published several academic papers on houseflies as vectors for diseases such as typhoid fever and cholera. In turn of the century wars (the Spanish-American War and the Anglo-Boer War specifically), more soldiers died of typhoid than as a direct result of combat. Major Walter Reed established that after human-to-human exposure houseflies were the greatest typhoid spreading agents. Soon after houseflies were linked to the spread of cholera.

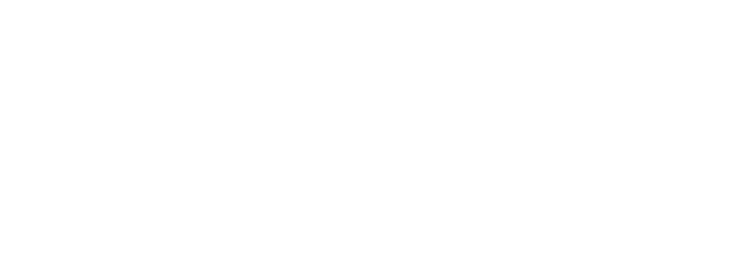

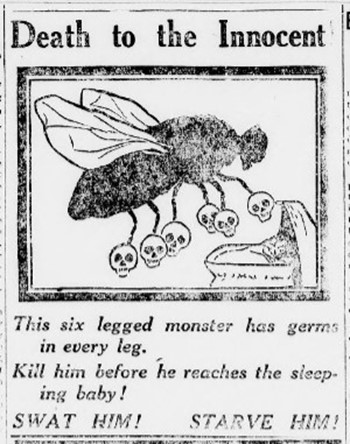

The housefly as a vector for typhoid and cholera was well established by 1916, so what changed? The polio outbreak of 1916. In the spring and summer of 1916, 27,000 people contracted polio in just New Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New York, nearly all of whom were under the age of five. Since houseflies were already known disease carriers, they were a convenient scapegoat. Anxious and terrified parents now had something they could actively do: wage war on flies and save their children. For the 1917 spring and summer the “Swat the Fly!” campaign was launched by public health departments and civic organizations across the country.

Notices like this appear in the Brevard News through the summer months, and then disappear as the weather cools. The Brevard Betterment Association even offered a bounty on houseflies. Fly hunters were paid twenty cents for each pint jar filled with dead flies, and forty cents for a quart. The ads resumed in 1918, but not as frequently as the year before.

Perhaps fly hunting turned out to be harder than expected, or maybe the Betterment Association ran out of money, but by 1919 the message had shifted from killing the flies in your house to stopping them from breeding. The following announcement was placed in the “Brevard News” on July 18, 1919: “You cannot kill all the flies. You cannot keep all those not killed out of the kitchen or dining room in summertime. But you can curtail propagation. Clean up your stables, barn, hog pens and back yards, then purify same with fresh lime- it will beautify the town and prevent disease” T.H. Galloway, Mayor.

Despite anti-fly campaigns and even use of pesticides to control houseflies, polio cases continued unchecked. Although typhoid vaccines had been available in the US since 1909 and required for all US military forces starting in 1911, they were not widely available for the general public until around 1920. According to the CDC there were 34 cases of typhoid per 100,000 people in the US in 1920, which was down from 100 per 100,00 in 1900. By 1940 there were less than 8 per 100,000. With the steady decline in typhoid and polio continuing regardless of the anti-fly lobby, public interest in waging was on houseflies waned. Houseflies were still suspected as possible vectors, but it was not until 1948 that a large-scale study in Texas determined conclusively that community-wide fly control had no impact on the number of polio cases. Finally, houseflies could live in peace.

As for polio, Dr. Jonas Salk developed the first polio vaccine which he tested on himself and his family in 1953 and following a one-year trial in 1954 on Canadian, Finnish, and US children, it was licensed in April of 1955. Within two years the number of cases annually dropped by more than 90%, and parents everywhere breathed deep sighs of relief.

Photographs and information for this column are provided by the Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library. This article was written by Local History Associate Hale Durant. For more information, comments, or suggestions, contact NC Room staff at [email protected] or 828-884-1820.