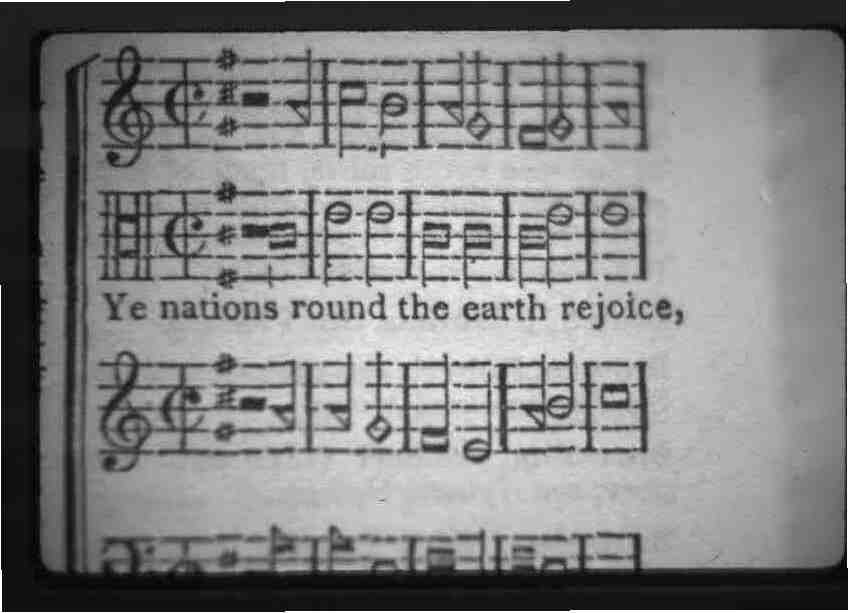

A form of sheet music that has been relegated to history is shaped-note singing. This unique form of sheet music common in many rural churches in the South in the 19th century and early 20th century was developed for church congregations in part to assist with illiteracy, though its benefits extend beyond that original purpose. Shaped-notes are similar to the musical notation that we all recognize with one immediately noticeable difference: the note heads are not all oval. Some of them are shaped like triangles, squares, or diamonds. Each of those symbols was associated with a different syllable, including fa, sol, la, or mi.

Because each note had a different shape, the sheet music viewer did not have to understand how to read a key signature, which is a specialized skill that takes time to learn. They could instead look at the shape of the note to understand how it connected to the notes before and after it. This style of singing also accommodated for the fact that there were no accompanying instruments to help keep the rhythm and unify the sound of a choir.

One other distinction between shaped-note notation and standard musical notation is that there are only four, and not seven, syllables. In standard musical notation the syllables do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti correspond with the notes of C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. In shaped-note notation, the scale progresses in this manner: fa, sol, la, fa, sol la mi. Those syllables do not correspond to specific notes; rather they are relational to one another, meaning they show how far apart the tones are but not which note to start on.

This style made it easier for a choir to choose their best key for singing and easily transpose from one key to another. Whatever key was chosen, the first “fa” would always correspond to that note, with the other note and syllable correspondences being determined by which note the song started on. The choir leader would calibrate the group by picking a starting tone, the group would go through the song once singing the syllables only, adjustments would be made if necessary, and then the group would sing the song in earnest using the lyrics.

Shaped-note sheet music would include all four harmonizing parts, and the melody would not always be led by the sopranos; it was often led by the tenors. In some churches, the song might even be performed in a type of call-and-response style that is used in liturgical music called “lining out.” This meant that the song leader would first sing a line and then pause for the choir to repeat the line. It was also common for the choir to be divided into soprano, alto, tenor, and bass with each section facing toward the center in an open square formation, with the choir leader at the center facing the tenors.

These singing traditions changed over time to what we would recognize church choirs to look and sound like today, but some of the remnants of this style can be seen in the division of vocal ranges into groups, such as in this picture of the First Baptist Church choir in 1957. Photographs and information for this column are provided by the Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library. This article was written by Local History Librarian Laura Sperry Gardner. For more information, comments, or suggestions, contact NC Room staff at ncroom@transylvaniacounty.org or 828-884-1820.