Importance of pottery

Pottery and broken shards have long been a lingering remnant of human civilization; vessels are an everyday object associated with permanent, stationary settlement. The reason is simple: pottery is not as easily transported as hides, gourds, or baskets. It’s heavy, can break, and has a process of creation that takes time, tools and equipment that would be challenging to move.

Although we often think of wheel-thrown ceramics now, that is a relatively modern invention. Hand-built pottery is the earliest type that humans have made for numerous reasons, including the fact that its manufacture was learnable for most people and materials could be found in nature. Through a process of trial and error, past makers honed the techniques of finding and preparing clay, creating pottery, and harnessing fire to harden and strengthen wares.

Pottery has been a mainstay of archaeologists attempting to understand past cultures because the materials added to the clay would often indicate the original source and location where it was harvested, therefore helping to identify the people who may have made it. Potters often followed the clay, looking for natural sources that would have the correct mix of minerals for their desired techniques. Additionally, clay is impressionable and easy to individualize with designs. This malleability has made it possible to see patterns in design that are common among communities and groups of people.

First American potters

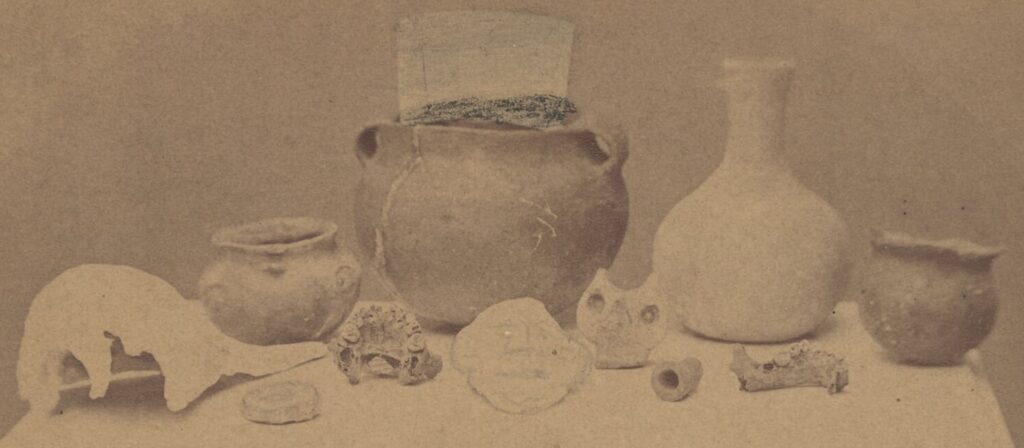

The first pottery makers in western North Carolina were the Cherokee, as evidenced by remnants dating back as far as 1000 BCE. Their style of pottery creation went through several distinct styles over the centuries, each characterized by common shapes and decorative motifs not unsimilar to the evolution of European art and the distinct styles that are representative of different eras.

Cherokee pottery characteristics

The Cherokee would begin a pot with their selection of clay mixed with other elements for desired effects. The composition of the “clay body”, or mixture of clays and other minerals, would be created by gathering different types of clay and other minerals, pulverizing them, mixing, adding water, removing impurities and foreign objects, and then either using the mass immediately to create an object or storing it for later use. Removing impurities and drying out water content was essential to prevent cracking and breaking during the firing process.

A pot was made with the pinch pot method to create a base that would be placed on a cloth if too large to handle while making. The cloth kept the pot from adhering to the building surface and allowed it to be moved without warping. The potter would then use the coil method to build the walls of their pottery by creating a long rope of clay that would be coiled into the outer wall shape, stuck to other clay elements with a mixture of clay and water called “slip,” and then smoothed out with hands, tools or both.

The shape of Cherokee pots had some common features. The base of Cherokee pottery was rounded, to allow it to be set on hot coals without covering up and extinguishing the fire. Later eras would sometimes add small feet to help larger pots stay upright. The rims were usually built up and slightly flared out to create a rim, which would reinforce the edge and prevent chipping.

Cherokee pottery often wasn’t fired at high enough temperatures to be impermeable to water. The fired pots were prone to collect water condensation on the outside. This was not necessarily seen as a negative thing – the condensation was known to carry heat away from the liquid inside, keeping it cooler. When techniques from European settlers were later incorporated into Cherokee practices, they fired with kilns and created a water-tight pot.

One very common technique often seen in examples of Cherokee pottery is stamping created with wooden paddles. A relief pattern would be carved into the wooden paddle which would be repeatedly struck upon the soft clay of a finished but not dry pot in order to leave decoration.

Paddle stamping also had a functional purpose; it would compact and thus strengthen the walls of the vessel, and the textured pattern provided grip. Burnishing or polishing would be the next step, if a part of the piece. The clay needed to be mostly dry before a smooth polishing stone would be rubbed in a circular motion over the surface of the clay to create a shiny finish. The clay couldn’t have any water in it at this stage, or the stone would leave markings on the surface.

Clay objects were then thoroughly dried before being fired to cause the clay particles to fuse together, making the vessel hard and durable. Cherokee would also use a smoky bark fire to “smudge” finished vessels on the inside, adding a shiny, blackened finish to the interior.

The story of pottery in western North Carolina will continue with the next article in the series. To learn more about the traditions of Cherokee crafts including pottery, basketry, and carving, an upcoming program “Cherokee Traditions” will be held on Thursday, May 2 from 6-7 pm in the Rogow Room at the Transylvania County Library.

Photographs and information for this column are provided by the Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library. This article was written by Local History Librarian Laura Sperry. Sources available upon request. For more information, comments, or suggestions, contact NC Room staff at [email protected] or 828-884-1820.